On Linguistic Relativity, Metalinguistics, Circularities, Personality Formation & Modulation, and Language Learning

14 November, 2023 – ex cathedra

Bruegel’s The Tower of Babel

“To have a second language is to have a second soul”

“Tu essaies de parler anglais, mais en français1,” admonished my French professor (who doubled as a linguist in her earlier years). As a life-long de facto monolinguist, I found this comment somewhat nonsensical. I value my ability to express myself in English. Linguistic expression is inextricably linked to one’s humanity and identity. In learning French, I intend to lose neither. Rather, I would consider it a resounding success if one day I could communicate with an equivalent fluency in French, which I retorted to my professor in so many words. She elaborated:

Parler couramment deux langues, c’est d’accepter d’avoir en gros deux personnalités2

This seemed both cryptic and psychologically disconcerting if I were to accept her advice. Was this to say the ever-elusive goal of bilingual “fluency3” was only attainable in conjunction with a DSM-V diagnosis of multiple personality disorder4? Of course, I’m presenting an absurd strawman here. Nonetheless my professor’s commentary remains poignant.

As I interpreted it, my professor was suggesting that I was directly translating my silent English thoughts into verbalized French words, albeit standard practice as one learns a new language. That is, I was using similar sentence structure and vocabulary while making idiomatic adjustments when necessary.

Yet, to speak a new language, as any multi-lingual person can attest, is not to calque, not to literally translate words from your native language to your target language – if it were, Google Translate would have caused professional translators to become obsolete ages ago. Instead, it entails adopting a new mode of expression and thought, and, indeed, a new personality (within limits). Cultural- and language-specific references and idioms, vocabulary, and language-specific structures will shape our self-expression, how we engage with others, and even our thought processes in a new language. Expression in a new language can be viewed as a metamorphosis of sorts – a function, f, specific to a given language pair, that transforms your normal personality x in your native language into personality y in your new language5:

f(x) = y

To be bilingual (or trilingual, quadrilingual, etc.), is to shapeshift between two (three, four, etc.) personalities. How fun!

I admit, this abstract discussion that you just joined me for, although perhaps an amusing thought experiment, is quite hand-wavy and non-substantive and a bit absurd. Linguistic literature does not, in fact, comment on links between multilingualism and multiple personality disorder.

Let’s shift away from the absurd toward the empirical. Regarding my French professor’s comments, I think she was playfully articulating the idea of linguistic relativity: that language affects our cognition; that we unconsciously vary how we express ourselves and view the world as a function of the language we are speaking6.

Linguistic Relativity: it’s Relatively Simple

Like most cocktails, religious schisms, and Class-A drugs, linguistic relativity comes to us in two forms: strong and weak.

The strong form, known also as linguistic determinism, asserts that, as the name suggests, language determines (or put differently restricts like a cognitive cage7.) thought, decisions, and acquired worldview8. The godfather of this theory, Yale anthropologist Benjamin Lee Whorf, argued, for instance, that certain American Indians were incapable of conceptualizing the future as their language had no future tense. He also contended that their language prevented them from conceptualizing certain objects for which they had no word. This theory was co-opted by the strain of pseudo-scientific 19th and early 20th century colonialist thinkers who were seeking to effectively masquerade blatant racism and virulent condescension as scientific thought9 à la The Great Gatsby’s Tom Buchanan10, and exploited these theories to promote racist ideas. In any case, modern linguists have largely discredited the strong form of linguistic relativity11.

The weak form massively hedges the claims of its browbeating brother, asserting much more modestly that language has a non-negligible influence on thought, decisions, and acquired worldview12. Put simply, language plays a non-trivial role in shaping our thinking13. Indeed, proving such a conjecture is not difficult, and linguistic research provides a wealth of empirical evidence to substantiate this very claim.

Language Projecting on the Universe: Color Perception

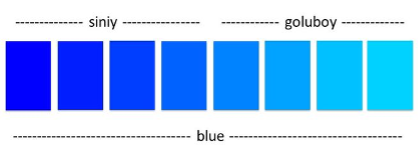

Perhaps the most tangible example of linguistic relativity is color perception. Languages differ substantially in how they categorize their principal colors. Welsh makes no distinction between the color of the sky, “glas,” the grass, “glas,” or the sea, “glas.” Russian draws an obligatory distinction between light blue “goluboy” and dark blue “siniy” whereas English (or French) does not.

Russian blues…

Studies have shown that Russian speakers can more quickly differentiate shades of blue (and are more adept at perceiving slight variations in blue) than English speakers, which researchers attribute to the more precise categorization of blue in the Russian language. These are but two examples among numerous, illustrating how a feature of language as arbitrary as its division of primary colors influences the perception of its speakers.

Language influences color perception, and color perception is a form of perception, therefore by syllogism we have that language influences perception. QED. We have proven the weak form of linguistic relativity. Shall we continue onto more lively examples?

Language Projecting on the Universe: Spatial Perception

Imagine you, an epicurean, are preparing a bacchanalian feast in celebration of Bacchus, with whom you closely identify14. You wish to explain to your benevolent friend who is helping you set the table that the champagne flute should be placed left of the red wine goblet and right of the water glass, however, you must do so without using the words “left” or “right.” As a speaker of an Indo-European language, this would seem rather mystifying, no?

You the epicurean at said bacchanalian feast, seated center, sporting a floral wreath, surrounded by your benevolent friends, carousing, gormandizing, and indulging in the pleasures of the flesh

Indeed, some languages lack the vocabulary for relative (or egocentric) directions like “left” and “right,” and instead rely on compass directions, such as the language of the Pormpuraaw aboriginal people of Queensland, for whom cardinal directions play a ~cardinal~ role in their language15. Rather than explaining to your Pormpuraaw friend that the port glass should be placed to the “left” of the sherry goblet, you would instead direct them to place it “west” of the sherry goblet if the place setting is oriented north, while on the opposite side of the table the port glass should be situated “East” of the sherry goblet given that the place setting will be oriented south. Even scribbling such a description was disorienting, let alone reading or explaining it…

As cognitive scientist Lara Boroditsky puts it, if you saw someone from the Pormpuraaw with an ant crawling up their leg, you wouldn’t warn them that there is ant on their left leg, but an ant on their north-west (depending on the compass directions) leg. Speakers of such languages that rely heavily on compass directions are able to orient themselves exceptionally well. Brodistsky proposes some level of causality here: when your language requires you to constantly note cardinal directional information, you are in turn developing this mental muscle, and you become better at orienting yourself16. This results in a 100% measurement difference in certain forms of perception between speakers of languages that rely on cardinal directions compared to speakers of languages that rely on relative directions – a child who speaks a language that relies on cardinal directions can always indicate northwest, while perfectly adept adults in western society certainly cannot.

Language Projecting on the Universe: Temporal Perception

Look at the Nestle advertisement below. Is there anything about it that seems abnormal to you? I would assume not given you are most likely an English speaker. However, this advertisement for a child nutritional supplement provoked widespread confusion when Nestle introduced it in Arabic- and Hebrew-speaking countries.

Nestle Advertisement for a Children’s Nutritional Supplement

Why the confusion… Languages vary in how they conceptualize spatial representation of time. Temporal progression generally mimics writing direction17. English (and nearly all Western languages) is written left to right, and time progresses in the same direction. This advertisement would make sense to speakers of these languages: a baby gradually gains range of motion over time as the images unfold. One could interpret the advertisement as suggesting that the consumption of such a product could promote a baby’s development.

However, for Arabic and Hebrew speakers, the advertisement is nonsensical. These speakers perceive time from right to left, in accordance with the direction of their written language. In this same publicity, a Hebrew speaker sees a child who begins standing, but then, after consuming this Nestle product, becomes gradually debilitated until it is left as an incapacitated newborn. Feeding a child such a product would be tantamount to child abuse!

How might a member of the Pormpuraaw organize time? When linguists asked them to organize pictures showing an aging person, they placed the cards from east to west. That is, if they were facing south, they would organize the cards from left to right, and if they were facing east they would organize the cards from top to bottom. Perhaps if Nestle ever wants to expand its reach to sell its baby supplements to the Porpuraaw people, they’ll have to devise a dynamic advertisement that adjusts the images based on its orientation…

One could argue that the Pormpuraaw construction of time is more logical than that of other languages. For these aboriginal people, the dimension of time is static, always unfolding from east to west regardless of one’s personal orientation, while speakers of other languages maintain a rather narcissistic view of time. Namely, that the entire dimension of time shifts every time one adjusts our body.

Language Projecting on the Universe: Gender Perception

So far, we’ve established that language influences our perception of objective concepts in our world such as color, space, and time (i.e., linguistic relativity). Although these differences represent interesting observations, one could hardly suggest that a slight difference in the delineation of primary colors, for example, has a significant impact on our interaction with and understanding of our world. However, how we perceive the gender of objects and people around us could.

We use nouns to mark every object in our world, and in Romance languages, all nouns have a gender – this is called grammatical gender. To illustrate this concept for those who are unfamiliar, we can provide an example from the French language. A chair in French, “une chaise,” uses the feminine article “une,” while a bridge in French, “un pont,” uses the masculine article “un.” Indeed, every noun in the language has either a masculine or feminine gender association.

If the gender of an object affects our perception of it, then these gender labels could have reverberating implications on how speakers of languages with grammatical gender interpret their environment. Russian linguist Roman Jakobson, who pioneered this research in the 1970s and 80s, asked Russian speakers to physically “act out” days of the week. In Russian, each day of the week has a grammatical gender, either male or female. Jakobson found that the personifications in his study matched the Russian grammatical gender of the day of the week (i.e., participants acted masculine when portraying Monday, Tuesday, and Thursday, which are masculine in Russian, and feminine when portraying Wednesday, Friday, and Saturday, which are feminine in Russian).

In the intervening decades, scholars have expanded on Jakobson’s work. Researchers in one study asked native German and Italian speakers to describe objects that had differing grammatical genders in the two languages. When asked to describe a “bridge,” the Italian speakers, for whom the word was masculine (un ponte), tended to use masculine descriptors, such as towering, strong, and sturdy, while the German speakers, for whom the word was feminine (eine brücke), were more likely to use feminine descriptors such as beautiful, elegant, and peaceful18.

When asked why these nouns had a specific gender, monolingual speakers suggested that it was because the objects were in fact inherently masculine or feminine – that the gender reflected the reality of the world, which may seem preposterous to an English speaker for whom nouns don’t have gender. In contrast, bilingual speakers demonstrated a certain metalinguistic awareness – these speakers, who had come to learn that genders sometimes disagree between languages, were much less likely to claim that the object reflected its gender, but rather that it was solely a grammatical feature of the language.

Allegory of Fortuna and Justice. The German monogrammist depicted justice as a feminine figure in accordance with the German grammatical gender of justice, “Gerechtigkeit”

As a final example of the impact of arbitrary grammatical gender on our perception of the world, I present to you a study where researchers examined how artists depicted personifications and allegories of objects. That is, these linguists wanted to investigate whether the language one speaks (and the grammatical gender assigned to the objects in one’s language) affects the way one imagines and depicts objects. Indeed, researchers were able to predict the grammatical gender of the object in the artist’s native language 78% of the time (i.e., if death is masculine in the artist’s native language, she is more likely to depict death as a man, and vice versa). Lara Broditsky, the lead researcher speaking to the results:

The size of this effect really quite surprised me because I would have thought at the outset that, you know, artists are these iconoclasts. They’re supposed to be painting something very personal. But, in fact, they were reflecting this little quirk of grammar, this little quirk of their language and in some cases, carving those quirks of grammar into stone because when you look at statues that we have around – of liberty and justice and things like this – they have gender. You know, it’s Lady Liberty and Lady Justice. Those are quirks of grammar literally in stone.

Such influence on our perception begins to manifest early in development. Research led by Alexander Guiora looked at how quickly Finnish, English, and Hebrew children could identify their gender. He found that children whose native language was Hebrew could identify their own gender about a year earlier than those learning Finnish. The researchers ascribe this effect to the substantial “gender-loading” in Hebrew compared to Finnish.

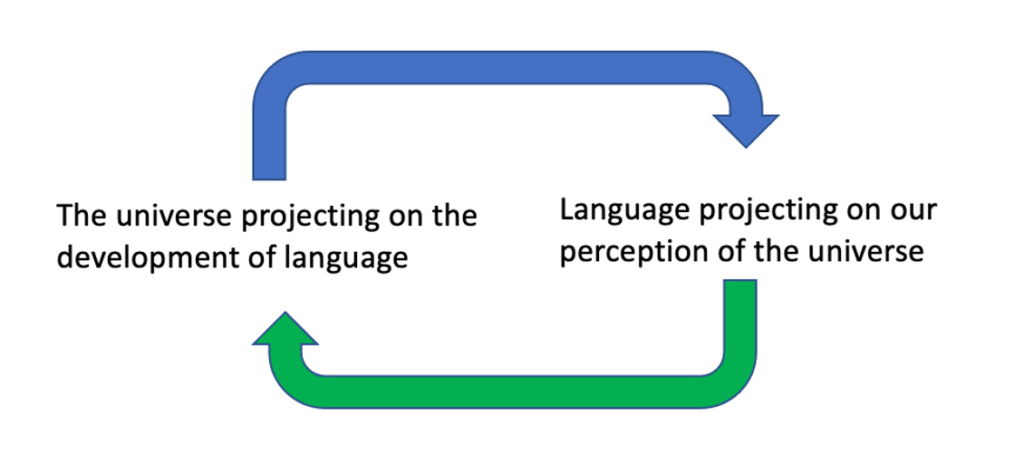

Interlude: The Universe Projecting on Language

To be sure, this interaction that exists between the exterior world and language functions in both directions. As we’ve seen, language shapes how we view our environment, yet, our environment undoubtedly must shape the development of our language, too. None of this should be particularly revelatory.

The circularity of language, pt. I

As a simple illustration, one would expect vocabulary to vary based on local communicative needs. For example, certain sub-saharan African languages did not historically have a word for snow, whereas Benjamin Lee Whorf (the notorious father of linguistic determinism, v.s.) (in)famously averred that the Yupik and Inuit languages (of the “Eskimos”) had c. 50 words for snow19 . In these instances, we can rightly infer that these languages were influenced by the ecological niches of their speakers. Indeed, researchers recently revisited the Eskimo snow question (“Hoax”) using more robust methodologies and found that languages that have collapsed the distinction between ice and snow are spoken exclusively in warm regions while languages that differentiate between the two tend to be spoken in colder regions.

A growing amount of research has shown that cross-linguistic differences often match variations in topography, population size, and other social, physical, technological, and environmental factors. Researchers have linked environmental factors to a language’s color lexicon (e.g., languages whose speakers live in higher latitudes and near large bodies of standing water are more likely to have different words for “green” and “blue”) and phonetics (e.g., languages whose speakers live in more humid climates generally have a greater reliance on vowels)20. They have also found associations linking population size and number of adult learners of a language to language complexity, suggesting languages may adapt to the cognitive constraints of their speakers and the sociolinguistic niches of their speakers (e.g., languages spoken by large populations with many language learners have more predictive rule systems than those spoken by smaller populations21, as well as simpler inflectional morphology22).

Returning to our discussion of spatial perception and the Pormpuraaw people of New Zealand, linguistic researchers find that languages dominant in industrialized, urban communities tend to favor relative (“egocentric”) spatial relations like “left” and “right,” while languages dominant in more rural regions prefer either (i) local environment-based spatial relations like “uphill,” “downriver,” “oceanward,” or “lagoonward” or (ii) cardinal directions. Linguists infer that a mixture of factors including topography, population structure, and prevalence of non-native language learners influence the development of these differing systems of spatial relations.

Before moving forward, it’s important to note that this research is cross-sectional and thus demonstrates correlations between environmental factors and linguistic features rather than causal links23. However, scholars have hypothetically inferred some influence of the former on the latter24, and note that “linguistic conventions are likely to be continuously shaped by a meshwork of multiple cultural, historical and cognitive factors working on multiple time scales.”

Language Influencing Culture and Behavior

Until now, we’ve established the presence of a circular relationship between language and environment using objective environmental inputs: identifying and categorizing color, time, gender, and space. As we discussed in the circularity of language, language projects onto our perception of our environment, and our environment projects on the development of our language.

However, can we arrive at more interesting conclusions from this relationship connecting language to the more amorphous and subjective – is there evidence that language influences our biases, our personality traits, or how we interact with others? Does language influence our culture? Given that the dependent variable in this relationship – biases, personality, social behavior – are so incredibly subjective, work in this area rests more on hypothetical inference rather than causal evidence. Nonetheless, the discussion remains thought-provoking and worth exploring.

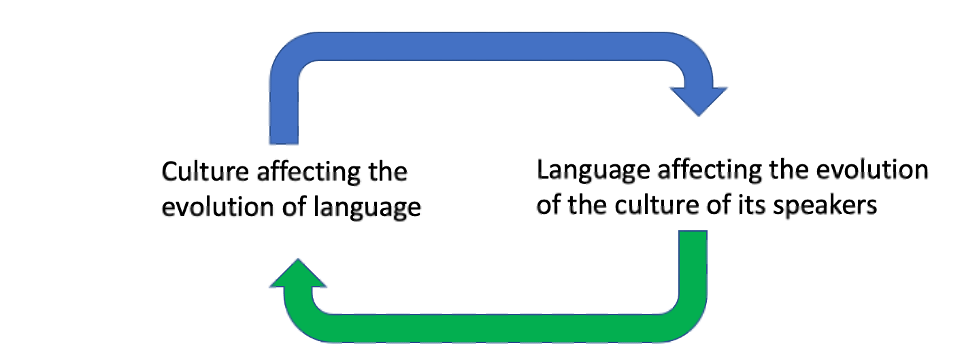

Moreover, bear in mind that in this subsequent discussion we will arrive at a second reciprocal relationship and potential circularity: is it our culture that is shaping our language, or is it language that is shaping our culture? Researchers have not generally been able to prove unidirectional causality.

Communicating Agency and Blame (J’accuse ! or Donald broke the 2nd century CE statue of Herodotus and has been indicted by a Federal Grand Jury!)

Does language affect how we assign agency and culpability of actions and remember the agents involved in events?

Let’s imagine a group of English and Spanish speakers visiting the Greek and Roman sculpture court of the Met in New York. Man #1, let’s call him Donald, picks up the 2nd century CE marble bust of the great Greek historian, Herodotus, and tosses it onto the ground, shattering it. Bedlam ensues. Shocked and disoriented by the sudden cacophony, man #2, let’s call him Joe, stumbles backward from the scene and bumps into the 1st century CE statue of Dionysus leaning on a female figure, causing it to fall over and shatter. Sounds like quite a tragicomic, entropic scene of classical chaos.

Dionysus leaning on a female figure, or “1st century CE Toxic Masculinity”

Now let’s assume that everyone else in the Greek and Roman sculpture court is either monolingual Spanish or English speaking. Researchers have found that the Spanish and English speakers would likely communicate agency in the two events (the former being intentional, the latter being accidental) differently.

In our example, let’s imagine that ex post, all the witnesses in the Greek and Roman sculpture court that day are brought before a federal grand jury in Manhattan to outline the events that led to this tragic outcome for our classical heritage. Both the English- and Spanish-speaking witnesses would likely describe Donald’s actions similarly, saying “Donald broke the statue” (“Donald rompió la estatua”), linking the agent involved (Donald) to the action (the broken statue), thereby framing the action as intentional. However, the two groups would likely differ in how they describe Joe’s actions. The English-speaking witnesses would likely once again use an agent-centric description such as “Joe bumped into the statue” or “Joe accidentally broke the statue.”25 Spanish-speaking witnesses, in contrast, would likely remove the agent in describing what transpired, saying perhaps “se rompió la estatua,” 26 thereby tacitly framing the action as accidental.

With these cross-linguistic differences in communicating agency in mind, linguists set out to test how English and Spanish speakers remember agency in accidental versus intentional events. Their study showed that, while both groups described and remembered the agents involved in intentional events similarly, the English speakers had better retention of the agents involved in accidental events. The researchers concluded that the patterns of our language are linked to how we remember events, even when no speaking is involved (the participants never had to describe the event during the memory task). The authors present several hypothetical explanations for these results: (i) participants were generating spontaneous “sub-vocal” descriptions of the events as they transpired, or (ii) our language’s preference for more agentive or less agentive descriptions shapes our attention biases.

These findings have important individual and societal implications. Researchers already know that the linguistic framing of an event impacts how we assign blame and mete out punishment.

Let’s return for a moment to our federal grand jury sitting in the federal courtroom in downtown Manhattan, reviewing witness testimony from our chaotic trip to the Met’s Greek and Roman antiquity collection. Regardless of whether the grand jury heard testimony from the Spanish- or English-speaking witnesses, it would undoubtedly indict Donald for high crimes and misdemeanors against the late, great Herodotus.

In Joe’s case however, one may expect the jury, after solely hearing the accounts from the English-speaking witnesses, to place greater blame on Joe for accidentally shattering the statue of Dionysus, and advocate for a more severe punishment, than it would after solely hearing accounts from Spanish-speaking witnesses.27 How might English-speaking societies differ from Spanish-speaking societies more broadly in how they interpret shame, guilt, and blame, and mete out judicial punishment?28

Gender Inequality

Earlier we saw that grammatical gender in a language may impact how we view the objects around us. How else might grammatical gender be shaping our interaction with the world? A perennial question in linguistics asks whether gendered languages (i.e., languages that use grammatical gender) contribute to gender biases and gender inequality writ large. There is abundant evidence indicating that countries in which gendered languages (e.g., romance languages, Slavic languages, etc.) are dominant suffer from greater gender inequality “in labor, credit, board membership, division of household labor and education… and are associated with more regressive gender norms… than are countries whose languages feature gender-neutral grammatical systems.” From the World Bank:

Grammatical gender is associated with a nearly 15 percentage point gap in female labor force participation relative to men, even after controlling for various geographic and economic factors that could be driving the difference. In practical terms, gendered languages could account for 125 million women worldwide being out of the labor force.

Thus, we see in the literature a wealth of evidence supporting a correlation between gendered language and gender inequality. Researchers have recently sought to find causal evidence of this link. In one study, researchers first noted that the gender gap between high schoolers in mathematics was much larger on average in countries with gendered language than those with genderless or gender-neutral languages. In their study, the authors had high schoolers either take a mathematics exam in which the test-taker was addressed in either the masculine or feminine. The authors found that addressing female test-takers in the feminine and male test-takers in the masculine reduced the gender gap by a third, i.e., the female test-takers who took exams that addressed them in the feminine performed better and spent longer on the exam (a proxy for effort).

None of this, of course, is conclusive evidence that gendered language is causing widespread gender inequality across certain societies, although undoubtedly there appears to be some link.

Universalism

Researchers have found that people who speak languages that omit pronouns (i.e., don’t use pronouns “I” or “you”, such as Japanese) tend to have more collectivistic values, while speakers of languages that do not allow the omission of pronouns (such as English) tend to have more individualistic values.

Although these researchers from the 1990s posited that it was the explicit, required differentiation between “I” and “you” in these languages that results in more individualistic thought within a culture, scholars have revisited these findings, arguing that it could be just as likely that it is the reverse: that more collectivist values within a society may drive its speakers to be systematically more lenient in the omission of pronouns, and vice versa.

The circularity of language, pt. II

This leads us to a derivative of the circularity of language that we discussed earlier: we can imagine a circular relationship where language affects the evolution of our culture, which in turn affects the development of our language. What is more, both language and culture are sure to influence human behavior, perception, and worldview.

Politeness and Honorific Systems

We can identify this same reciprocal relationship between culture and language in linguistic honorific systems29. East Asian languages, such as Japanese, Korean, and Chinese, have an advanced system for varying the formality of their communication by employing honorific forms of vocabulary and syntactic structure, which English lacks30. Indeed, studies have shown that Koreans were more likely than their American counterparts to change the register of language and communication style based on the social status of the person with whom they were speaking.

One must therefore ask, (i) is East Asian culture more hierarchy-oriented, and its speakers more likely to employ honorific expressions, because of their language, or (ii) did East Asian languages simply encode over time these honorific structures of politeness because of the culture and worldview of the speakers, thereby reflecting culture? In any case, the honorific system within these languages today surely facilitates the hierarchical worldview of their speakers.

Savings and Future-Oriented Behavior

As a final example, we will look at how a language’s grammatical marking of future events may affect the behavior of its speakers. Many languages, like English, require the use of a future tense when describing or predicting future events (“It will rain” or “It is going to rain”) while others, like German or Mandarin, do not (“Morgen regnet es” in German literally translates in English to “it rains tomorrow”).

Researchers have found that speakers of languages (such as German) that do not grammatically necessitate the future tense when expressing the future “save more, retire with more wealth, smoke less, practice safer sex, and are less obese” than speakers of languages that do necessitate the future tense. They theorize that grammatically differentiating the present and future (as does English) causes speakers to perceive the future as more distant, rendering future-oriented behaviors that involve delayed gratification more difficult. In contrast, when a language equates the present and future grammatically (as does German), its speakers are more willing to delay gratification and embrace future-oriented behaviors since they perceive the future as closer.

Although these findings held not just across countries but within countries where multiple languages were spoken, one cannot deny that these differences may be due to cultural factors or that the causality may be functioning in the opposite direction.

Language and Personality

The end of these seemingly endless ramblings draw nigh, yet we’ve arrived here without addressing the motivating question proposed at the outset and it behooves me to do so: do the languages we speak shape our personality31. This question must be further broken down into four versions:

(i.a) Language-Driven Personality Formation amongst Native Speakers

(i.b) Language-Driven Personality Formation amongst Non-Native Speakers

(ii.a) Language-Driven Personality Modulation amongst Native Speakers

(ii.b) Language-Driven Personality Modulation amongst Non-Native Speakers

In (i.a) and (i.b) we are asking whether language impacts the formation of personality for native and non-native speakers. In (ii.a) and (ii.b) we are asking whether changing from one language to another causes a modulation in the personality of a multilingual individual.

For our purposes let’s assume a native language is a language that an individual is exposed to and acquires fluency in during their childhood. This could be a single language – for example, an individual who grew up in Seoul (a Korean-speaking environment) in a monolingual Korean household and attended Korean-speaking school – or several – for example, an individual who grew up in Barcelona (a Spanish- and Catalan-speaking environment) in a German- and Japanese-speaking household and attended an English-speaking international school.

Let’s assume a non-native language is a language one acquires post-childhood (after the age of 17). We must also assume that the individual speaks the acquired language with bilingual fluency, otherwise, it could be their relationship with the acquired language (e.g., inability to express themselves, discomfort with the language) rather than the language itself that is manifesting through a change in personality traits (increased introversion being a classic example).

Language-Driven Personality Formation

Does language fundamentally shape our personality, or more precisely our perception of the world, structure of thought, and behavioral and emotional responses to the stimuli around us32? Put differently, are the structures of our language encoded into the structures of our mind, making us more introverted or extroverted, sociable or anti-social, agreeable or abrasive, selfish or selfless?

Indeed, we have already explored evidence in support of this claim! We saw the elaborate honorific systems in East Asian languages could make its speakers more deferential to authority and hierarchy-oriented. Languages that omit personal pronouns like “I” or “You” could engender collectivist values in their speakers. Languages that use the same tense for the present and future may lead their speakers to have greater future-oriented behavior. In one example, we saw how the norm in the Spanish language (and other Romance languages) of removing agents when describing accidental actions may lead these speakers to be less accusatory. And of course, there is the canonical (and equally controversial) example of those arguing that grammatical gender in certain languages leads to gender biases and stronger gender associations.

Amongst native speakers, these various structures inherent to the languages they speak are mentally hardwired and surely manifest in the personality of the native speaker. Thus, we accept (i.a) language-driven personality formation for native speakers.

Amongst non-native speakers, one strains to craft an argument that the isolated act of learning a new language as an adult has the effect of re-hardwiring their brain and thus substantively altering their personality33. The process of learning a language and the experiences and interactions this newly acquired language facilitates could impact personality, but it wasn’t the language itself doing the job. Thus, we reject (i.b) language-driven personality formation for non-native speakers.

Weak Form of Language-Driven Personality Modulation

Let’s accept the premise that personality is a function of nature and nurture. Within nurture, there exist myriad environmental forces, two of which are surely language and culture. Here we run into the impossible feat of disentangling language and culture – when speaking a language which factor is influencing our behavior: (i) the culture and experience we associate with that language or (ii) the language itself?

Researchers have found that bilingual speakers, when switching from one language to another, exhibit different personality traits that align with the traits commonly associated with the corresponding language. Researchers call this cultural frame switching. Language influences our personality insofar as we absorb and exemplify the cultural values associated with the language. I view this more as a change in language facilitating a shift in mindset rather than a shift in personality – we associate certain cultural values with a given language (based on the context where we learned the language) and manifest those associations when speaking the language. Perhaps it’s the assertiveness of American culture when speaking English, the elegance of French culture when speaking French, or the machismo of Cuban culture when speaking Spanish. Let’s call this the Weak Form of Linguistic-Driven Personality Modulation. As one writer put it:

It may also be that the context in which you learn a second language is essential to your sense of self in that tongue. In other words, if you’re learning to speak Mandarin while living in China, the firsthand observations you make about the people and culture during that period will be built into your sense of identity as a Mandarin speaker. If you’re learning Mandarin in a classroom in the US, you’ll likely incorporate your instructor’s beliefs and associations with Chinese culture along with your own—even if those beliefs are based on stereotypes. And if you learn a language without any kind of context, it may not impact your personality much at all.

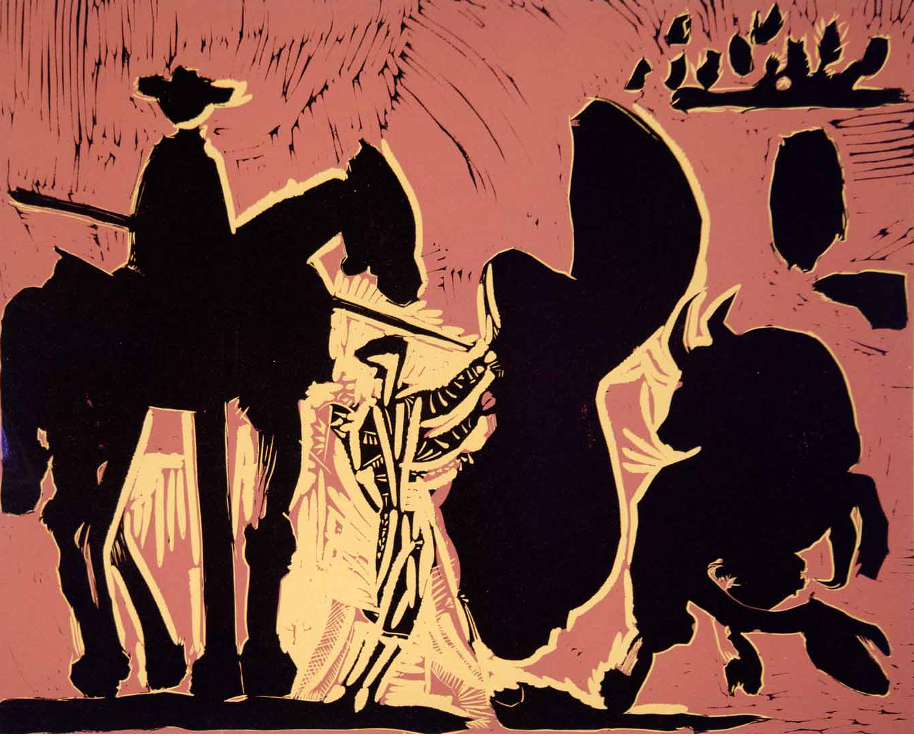

Avant la pique… Just because you speak Spanish does not make you Cayetano Ordóñez

I think we can safely conclude that both native speakers and adult learners can exhibit some level of personality shift via cultural frame switching when changing from one language to another. However, this seems to be a rather superficial personality shift, as if it could be (i) a mannered behavior34 or (ii) a product of code-switching, comparable to a Californian who moves to London and begins saying “rubbish bin” rather than “trash can” and “trousers” instead of “pants”35 and adopts a more ironic sense of humor, a more sardonic demeanor, and is generally less sentimental when socializing with peers in London, but reverts to his former personality when socializing with fellow Californians or family.

Thus, we accept a weak form of (ii.a) and (ii.b) language-driven personality modulation: that language has a superficial influence on mindset, behavior, and demeanor for both native and non-native speakers when shifting from one language to another.

Strong Form of Language-Driven Personality Modulation

Now we reach the holy grail of this discussion and the raison d’être of this very essay: to either confirm or refute my professor’a assertion that “Parler couramment deux langues, c’est d’accepter d’avoir en gros deux personnalités”. Do multi-lingual individuals truly possess multiple personalities, not merely through superficial shifts in mindset arising from language-specific associations, but rather through more profound, mentally encoded mechanisms? When a multi-lingual individual changes from one language to another, do they also change fundamental aspects of their personalities?

Let’s take once again our Barcelona-raised German and Japanese child who attended an international English-speaking school. What happens to her when she switches from Catalan to English? We should still notice the impact of the Weak Form of Linguistic-Driven Personality Modulation. Perhaps her associations with Catalan are convivial and familiar, as it’s the language she’s always spoken with friends, while her associations with English are more academic, hierarchical, and formal, as it’s the language she’s always spoken and written in the academic environment. Those associations may manifest through slight shifts in perception, demeanor, and personality.

However, we may also observe more deeply ingrained sources of her personality modulation – the causes and resulting behaviors we discussed in the section on Language-Driven Personality Formation, such as being more future-oriented when she speaks German, or more deferential when speaking Japanese, or less accusatory when speaking Spanish because with each shift in language, she leverages different neural pathways and views the world with a different mental model. These are just hypothetical examples, and the true consequences of shifting languages could extend across ideology and value systems and have yet to be empirically proven.

Thus, we accept the strong version of (ii.a) language-driven personality modulation for native speakers and reject the strong version of (ii.b) language-driven personality modulation for non-native speakers36. There was some truth to what my professor was saying, it just didn’t apply to any of the students in the class when they spoke French.

Discussion

In this essay, we’ve uncovered two fundamental circularities in language. In the first, language sits between us and the external world, concurrently shaping how we view our environment but also being shaped by our conception of our environment. It is in the first part of this circularity that we proved the weak form over the strong form of linguistic relativity. It is not that language acts as a “cognitive cage,” restricting our thinking, but rather as a cognitive code of conduct that obliges us to include certain elements in our thinking, thereby exerting influence on our cognition, memories, worldview, associations, etc.37

Russian obliges its speakers to discriminate between light and dark blue, improving their ability to differentiate shades of blue. The Pormpuraaw language obliges its speakers to use cardinal rather than egocentric directions, endowing them with preternatural orientation skills. Hebrew is read right to left, causing its speakers to similarly conceptualize the passage of time from right to left. Romance languages use grammatical gender, shaping the associations their speakers hold for everything from inanimate objects and animals to abstract concepts and professions.

The second circularity then provides a corollary to the first: language sits between us and our culture and values, concurrently shaping the development of our culture but also being molded by our culture. Spanish allows its speakers to easily remove agency from accidental actions, potentially influencing how they interpret guilt, assign punishment, and recall events. Structural biases intrinsic to languages with grammatical gender potentially contribute to gender biases or gender inequality. The omission of the pronouns “I” and “You” in Japanese contribute to collectivist mores.

One could also convincingly argue that if causality were to exist in these relationships, it could be functioning in the opposite direction (cultural values shaping the development of languages instead of language shaping cultural values); for example, tendencies toward deference and respect for superiors, and strict cultural hierarchies in Korea may have contributed to the development and continued presence of an expansive honorific system within the language.

In both circularities, the forces at play co-exist in an entanglement, obscuring the direction of influence and potential causality.

Lastly, we found that languages play a role in forming one’s personality (for native speakers) and that multilingual individuals may demonstrate different personality features when shifting between languages38.

Ultimately, what we’ve reinforced throughout this piece is the deep interplay between language, culture, and cognition and in particular the profound influence language has on our perception of and emotional reaction to the world, our culture, and indeed even our personality. What is more, researchers have only begun to unveil the full extent of language’s role in shaping our values and beliefs.

Epilogue: An Ode to Language Learning 39

As cynical as this discussion may have been at times, I remain steadfastly optimistic of the distinctly positive impact learning a new language can have on an individual. Although learning and speaking a new language perhaps does not recast us into wholly different individuals, I remain confident in the benefits of language learning.

We constantly face ideas, emotions, tastes, and stimulations that verge on the indescribable given the limits of our language and our own vocabulary. New languages provide us access to new words and expressions – new ways to conceptualize and describe our environment and our interactions with it. Indeed, in many cases, we see English import these “loanwords” from other languages when it lacks the concept itself. Among the slightly recherché 40 loanwords and expressions in English we have the German Weltschmerz, Schadenfreude, and Zeitgeist, the French carte blanche, bête noire, de rigueur, and sang-froid, the Italian cognoscenti, omèrta, and sotto voce, to name but a few, all without proper English-rooted equivalents41. Among the more common we have words such as café, tsunami, kindergarten, or many of your quotidian foods of foreign origin such as pasta and croissant.

However, there are many concepts that remain outside of the language of the anglosphere that have yet to be introduced as loan words. These include the German “Bildung,” the tradition of lifelong self-cultivation and upbuilding of the soul that goes beyond discrete vocational training as a means to an end; the Japanese “Komorebi,” the phenomenon of sunlight leaking through trees42; the French “dépaysement”, the sense of strangeness and disorientation one feels in a foreign environment; or, one of my favorite examples, the German “fuchsteufelswild,” which literally translates to “fox-devil wild,” meaning crazed, feral anger. Moreover, one may find that they can express certain ideas better in certain languages – that is, certain languages are better suited for specific uses, as Holy Roman Emperor Charles V infamously alluded to when he said “I speak English to my accountants, French to my ambassadors, Italian to my mistress, Latin to my God, and German to my horse.”

This is all to say, to speak another language is to access a new world of words and expressions; to enrich your thoughts.

Most importantly, language is the sine qua non of understanding a culture and its people43. For example, to attempt to fully understand the Italian people, culture, history, and politics without speaking Italian is futile. Without the capacity to speak the language, one is but a spectator, forever cursed to superficial connection and comprehension. To learn another language is to enlarge one’s world and enrich one’s interactions with broader portions of humanity. That language and monolingualism can prove to be an impediment to progress and cultural interaction is no recent observation. In the biblical story of the Tower of Babel, God prevents the Babylonians from building their tower to heaven by confounding their speech.

With the ever-rising dominance of English as today’s lingua franca, existence has become something of a tale of two cities for its native speakers – “it was the best of times, and it was the worst of times,” it was the age of cosmopolitanism, it was the age of philistinism, it was the epoch of accessibility, it was the epoch of cacophony, it was the spring of empowerment, it was the winter of debilitation.

It was the best of times for English speakers who have less need than ever to learn other languages. 1.35bn people speak English as a native or second language. In the developed world, the vast majority of people you interact with will have a basic level of English. You can exist in English, nearly everywhere, opening the world and its diversity of people and culture to you, as an English-speaker, like never before. It has eliminated enormous friction that has stymied travel and cross-cultural interaction since time immemorial. It is extraordinarily empowering. Indeed, speaking English natively – to be natively proficient and fully expressive in the world’s most dominant and arguably important language by chance – is akin to a superpower.

Yet, it was the worst of times for English speakers as it’s never been more challenging to learn another language. Or rather, as an anglophone, it’s never been easier to be lazy. You can visit and even live in distant foreign lands without learning more than the local words for “hello” and “thank you.” Even those rudimentary expressions are beyond necessity. You will strain to find a place where you cannot “get by” solely in English44. In many countries, the high level of English fluency amongst the local population (the Netherlands, Germany, the Nordic countries) will inhibit you from learning their language – as soon as they sense you are not native, they will reflexively switch to English. Because of the dominance of English, learning another language as an anglophone today requires more mental willpower and discipline than ever. Tragically, most English speakers today, either out of laziness or frustration, limit themselves to the imposed strictures of monolingualism. Moreover, as many commentators have noted it is of little surprise that it was the English and the Americans who have rejected internationalism for isolationism in recent years, both of whom have some of the lowest levels of second-language learning.

At the risk of descending into platitudes, I would encourage the reader to set themself upon further language acquisition. Even if you are already bilingual or multilingual, the returns are by no means diminishing – the acquisition of each new language remains just as intellectually fulfilling and stimulating, allowing you to engage with a hitherto unexplored and inaccessible world. And lastly, for the monolingual English speakers reading this, I assure you that you will never understand your own language and the rules it imposes on you until you speak a second.

Footnotes...

- "You’re trying to speak English, but in French!"

- To speak two languages is to accept that you have two personalities

- Rest assured, I detest this word as well. It is hollow, it is meaningless, it’s a word cavalierly tossed around by charlatans and snake oil salesmen to either (i) convince you they’re better than you and if only you followed their instructions you too could be an octolingual polyglot, or (ii) sell you some third-rate junk: “How I got fluent in French in 30 days”, “How I learn any language in 24 hours” (if anyone thinks they can learn a language in 24 hours, best to prematurely admit them to the nearest psych ward). Don’t get me started on the purported polyglots across the Internet these days…

- reducto ad absurdum, is that to suggest (dubiously) purported polyglots have five, ten, fifteen personalities that are in constant flux?

- I do realize this the mathematical equation here is a bit superfluous

- To be cognizant of these differences, to analyze and understand the nuances of the different languages you speak and how they affect your expression, is metalinguistic awareness, the old-school type of meta of Kant and Nietzsche rather than Mark Zuckerberg’s bastardization.

- Just because English doesn’t have a specific word equivalent to the German Schadenfreude or the Japanese Tsundoku (the act of buying books and leaving them piled up yet unread), doesn’t mean English speakers struggle to understand these concepts.

- Cf Wittgenstein: “The limits of my language mean the limits of my world”

- The logic was that “primitive languages,” as these writers put it, were inferior to European languages, and deprived their speakers intellectually, and should therefore be eradicated (Léglise & Migge). Absolutely horrific stuff…

- “Civilization’s going to pieces… I’ve gotten to be a terrible pessimist about things. Have you read The Rise of the Coloured Empires by this man Goddard?... Well these books are all scientific… This fellow has worked out the whole thing. It’s up to us, who are the dominant race, to watch out or these other races will have control of things.”

- Moreover, the proliferation, and later debunking of these ideas left exploration of any form of linguistic relativity academically untenable as a subject of research for linguists, until the late 20th century when scholars began to revisit them.

- It almost seems that linguists hedged to the point of forming a meaningless conjecture… Of course, one can prove something as important as language has some non-negligible influence on thought!

- This also aligns with Wittgenstein’s view in the Tractatus that language is inextricably linked to reality, arguing that the world is defined and given meaning vis-à-vis language – the structure, vocabulary, and idiomatic constructions of our language affecting how we experience reality. My favorite example of Wittgenstein’s approach in action is his description of a “three-sided figure:"

“Take as an example the aspects of a triangle. This triangle can be seen as a triangular hole, as a solid, as a geometrical drawing, as standing on its base, as hanging from its apex; as a mountain, as a wedge, as an arrow or pointer, as an overturned object, which is meant to stand on the shorter side of the right angle, as a half parallelogram, and as various other things … You can think now of this now of this as you look at it, can regard it now as this now as this, and then you will see it now this way, now this.”

- Unfortunately you had to downsize the celebration this year (186 BC) after those damned self-righteous prigs in the Senate passed the Senatus Consultum de Bacchanalibus limiting the scale of your annual fête by law and under punishment of death. Nonetheless, you remain steadfast in your resolve to imbibe like it’s 201 BC and your uncle Scipio Africanus (you always called him Uncle Skipper growing up) just returned home victorious from the Second Punic War after decimating the Carthaginian forces.

- Here I lean heavily on the research of Professor Lera Boroditsky.

- Of course, one would expect other potential causal sources affecting directional capability, namely the environment. The Pormpuraaw live in the forest where they must constantly navigate, whereas those of us who live in most modern societies will often rely on technology (viz., Google Maps and other GPS services), stymying our directional development. And, like any muscle, when you don’t exercise it, it remains underdeveloped. Thus, it isn’t just that you are necessarily congenitally bad at directions, but rather that you never developed this capacity as your language and environment never demanded it of you. Tell that to your significant other next time they harangue you over your poor directional capacity.

- This section is drawn largely from Fuhrman and Boroditsky.

- In case you’re worried that bridges in Germany are en masse aesthetically different from those in Italy, the researchers ran the same tests on English speakers after teaching them an invented language where certain words had either masculine or feminine pre-fixes and arrived at the same results.

- Many critics argue this is a gross misrepresentation of the Yupik and Inuit language, and that there are far fewer words for snow in these languages than the original claim. This example is often viewed as “pop” linguistics and “serious” linguists generally avoid it as an example. However, the point still stands that there appear to be far more variations of the word snow in these languages than there are in European languages.

- Yes, the authors of these papers establish hypotheses of causality, but more research is needed to prove causal links.

- One possible explanation for this phenomenon is that large populations tend to have more L2 (non-proficient individuals who are learning the language) speakers who tend to generalize irregular rules and collapse them into regular cases and pass these changes onto subsequent learners.

- That is, how verbs are conjugated and how words are modified to express tense, number, gender, mood, etc.

- I would caveat this by saying that a team of researchers did run a randomized control trial in a laboratory on a limited group of participants and found that environmental factors within the game that participants played did impact their communication conventions.

- Scholars do not generally believe that variation between languages is stochastic (randomly developing over time).

- In English, non-agentive language here would sound evasive and awkward (cf, Reagan’s infamous “mistakes were made” comments in the 1987 State of the Union Address).

- This is the reflexive tense in Spanish that has no direct equivalent in English.

- An even more pressing question that remains to be answered: why did Donald choose to smash the Herodotus statue, and is there any significance behind Joe’s “accidental” breaking of Dionysus leaning on a female figure? These important inquiries are left to you, the epicurean.

- A rhetorical question, also left to the epicurean.

- As a simple example, in the honorific system in French, one uses the “tu” register (tutoyer) to speak to an intimate or peer or speak down to an adult or child, while one uses the “vous” register (vouvoyer) to address others formally. In other languages, such as Japanese or Korean, there are far more ways to vary the formality of speech.

- English of course has a formal and informal register of language but does not modify the form of nouns, adjectives, verbs, etc. based on register. For those interested in linguistic history, NB that Middle English did make a distinction between “thou / thee” (informal 2nd person singular) and “ye / you” (formal 2nd person plural), similar to the French “tu” and “vous”, respectively. By the 14th century, thou and thee were used to indicate familiarity with friends and peers, contempt of superiors, or superiority over inferiors, or to avoid ambiguity in expressing the singular. The plural ye and you, however, began to be used not just as the plural form but also to address superiors formally. By the 17th century, rising social mobility and mixing of social classes made it less clear whether one should address others in the formal or informal register, with most shifting toward the formal register to avoid impropriety, causing the use of thou and thee to decline. Eventually, the informal “thou” fell into obsolescence in English vernacular, its use considered impolite.

- Before proceeding, let’s acknowledge that there exist bountiful anecdotal responses to this question on the Internet. Let’s try to avoid these lest we descend into pseudo-scientific Buzzfeed-style logic.

- This is a derivative of Wittgenstein’s argument in his Tractatus that language is our reality, and we understand our reality through the languages we speak.

- Perhaps this could be true in extreme cases where the individual embeds themself completely in the new language and culture and undergoes extensive assimilation, rarely speaking their native tongue. But for the general case, this seems to be a fanciful claim and sodden with specious and motivated reasoning. Apologies to all the adult language learners who think they’re undergoing drastic personal transformation upon learning a new language! The act of learning Italian has not fundamentally changed your personality to become some “dolce far niente” espousing, “sprezzatura” embodying bon vivant. Such affected behaviors were your own personal doing…

- Imagine an American who learns Brazilian Portuguese thinking, “I now speak Brazilian Portuguese, now I will consciously exhibit stereotypical Brazilian personality traits.” It would be ridiculous to claim that it was the language that changed the individual’s personality!

- Trust the scribbler, you don’t want to make that mistake.

- As Adam Sandler put it in an SNL skit parodying an ad for an Italian tour provider describing the limited impact of traveling to Italy: “It you’re sad now you might still be sad in [Italy]… There’s a lot vacation can do… but it cannot fix deeper issues, like how you behave in group settings or your general baseline mood. That’s the job for incremental lifestyle changes sustained over time.” The same can be said for learning a language.

- Roman Jacobson described: “Languages differ essentially in what they must convey and not in what they may convey.” Here I would also note that the inspiration for this idea came from Guy Deutscher in the New York Times.

- Here I’d like to disabuse the reader in no uncertain terms of the farcical conjecture that learning a second language as an adult will fundamentally change their personality. An adult language learner may code switch and they may engage with different cultural values. They are not, however, undergoing a radical metamorphosis in their fundamental and long-ingrained personality traits (e.g., selflessness, extroversion, sociability), at least not due to the act of speaking the language itself.

- Many of the ideas in this section are pulled from Mary Osborne.

- voilà ! I swear the use of a French loanword to describe the frequency of loanwords in English was wholly unintentional

- Through my non-scientific accounting, I find that English has the most loanwords from (i) French, which are typically used in artistic, literary, and culinary, contexts and (ii) Latin, which are typically used in philosophical and legal contexts. These words generally mark a formal or literary register of language. French has many English loanwords, but tellingly (and comically) these are either used in business contexts or constitute slang… No need to theorize how the French perceive the English and Americans. Their language leaves little room for ambiguity on this question.

- Japonophiles will often observe the abundance of arcane, uniquely Japanese verbs and nouns for obscure concepts without equivalents in any foreign language

- Yes, this is the ne plus ultra of clichés, but nonetheless valid and noteworthy.

- Most non-native English speakers generally do not have this luxury. A Portuguese person who wishes to live or work beyond the border of Portugal and Brazil will almost certainly need to learn another language – perhaps another European language like French, Spanish, or German, and likely some English, too. Even those who choose to stay in Portugal will likely need to learn some fundamental English to interact with an international clientele. Here lies the cruel irony of the anglosphere – a Portuguese man, a Frenchman, and an Italian man walk into a bar in Lisbon… what language are they speaking? Most likely English, as it may very well be the only language they all speak in common. On a continent from which the solipsistic English have violently extricated themselves by democratic vote out fueled by a carnal desire to languish in isolation in their beer-sodden backwater, their language remains the common tongue.